In an interesting turn of events, i actually did NOT get this one as faulty. It was more to relieve one of my 828mk2's from rehearsal-place-recording duty, and on the other hand, i managed to get it for quite cheap. In the context of, faulty ones had similar asking prices, so there's that.

Same chunky-but-stylish(?) cast aluminium casing as its bigger siblings (828mk2/mk3 etc), just in a half-width 1RU size - same as the Audio Express actually. But you can find external photos all over the internet, and that's probably not why you're here anyway. So let's pop the hood, shall we?

Reasonably tightly-packed, all things considered, especially with the amount of (analog) ins & outs available. "Structurally", and considering it's the first of its kind, i guess one might call this a sort of "mk2.5". It doesn't have the fully-analog (and needlessly over-engineered) preamps of the 828mk2, nor the >50dB-gain mic preamps of the mk3 generation, but it still uses encoders for the mic gain adjustment. But no spoilers, this is only going by the descriptions in the manual...

In order to have a complete view of the mainboard, two of the daughterboards need to come off. First is the MIDI & DC-input, that's tucked away in the rear corner. I still haven't managed to get my head around how exactly the components on this board get soldered, mostly because the DC input socket partially overlaps the MIDI input connector, but on the bottom of the board... Regardless, the reason for this unit being DC-input-polarity-"agnostic" is the same as in the Audio Express we took a peek into, not long ago - a little bridge rectifier.

And then there's the analog output board, carrying the eight balanced outputs. Not much to write home about, only that the opamps used are JRC NJM4580's.

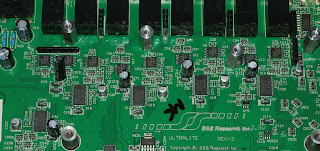

And finally, an unobstructed overall view of the mainboard. Not particularly cramped with components, it must be said, but that's not necessarily a bad thing. On the other hand though, there would have indeed been room for an extra feature or two, but that's neither here nor there.

Starting off with the power supply section, you'll be excused if it feels a bit like deja-vu - even though it's laid out differently, it is indeed strikingly similar to the Audio Express. A pair of OnSemi CS51414 buck-converters are in charge of the +3.3V and the +/-5.7V rails, respectively. Nearby is a pair of OnSemi LP2950A linear regulators, providing clean power to some of the less "grunty" digital chips. Also, a little Texas Intruments TPS730 provides the 2.5V rail for the FPGA (spoilers, sorry!).

Tucked away between tall capacitors and inductors, and under ribbon cables, is a little Texas Instruments TPS61040 boost-converter, handling the phantom power supply.

Really getting into the meat of it now, with the biggest slabs of silicon on the board. Running the whole show is an NXP LPC2104 (previously encountered in the 8Pre - no major coincidence, i'm sure), with an SST25VF040 4Mbit / 512Kbyte flash chip containing the settings, and possibly some part of the firmware. The Xilinx XC3S200 FPGA does the heavy lifting of manipulating and wrangling all the audio data around, while a Texas Instruments TSB41AB2 handles the Firewire interface. Another pair of Texas Instruments TPS730 linear regulators provide a 1.2V and a 1.8V rail to the FPGA.

In the middle of it all (more or less) is another MOTU favourite - a Texas Instruments TLC2933A PLL, providing audio clocking and synchronizing to the whole thing.

One more regulator, this time powering (i'm suspecting) the analog side of the converters, namely a Texas Instruments TPS796, set for a 5V output. And speaking of the converters - an AKM AK4382A handles the headphone output on the front panel, assisted by an NJM4580 and an ST Microelectronics TS922.

As for the rest of the analog ins and outs, a quintet of AKM AK4620A stereo codecs are on the job. NJM2115's seem to be the line input buffers, while NJM4580's constitute the post-DAC filter stages.

And this gets us to the more interesting, if not even arguably "cheating" part of this device, namely the mic inputs. You might notice the lack of anything like a PGA2500 digitally-controlled preamp chip, as seen in the "mk3" units. Also, if you carefully read the specs, you'll note the mic inputs only have a "measly" 24dB of gain. That being said, they also have a three-position pad switch (no attenuation / -18dB / -36dB). Between the latter and the quoted 24dB of gain available, nets a gain range of 60dB, which is somewhat conventional, if not even standard. The converters have built-in, digitally-controllable attenuation, as well as a programmable gain amplifier ahead of the ADC stage.

What i can "decode" from the circuit though, is quite clever, if not even ingenious. The mic inputs seem to feed straight into a pair of fixed-gain instrumentation amplifiers (the two-opamp variety), embodied by two NJM2068's (U13 and U34), while the instrument inputs are buffered by the third NJM2068 (U48). Not quite sure whether the pads affect the instrument inputs as well though, but they may very well not.

To be fair, while dynamic mics can use quite a bit of gain in order to reach some useful levels ahead of the analog-to-digital conversion, condenser mics don't necessarily need much help to reach, in some cases, even line-level signal amplitudes (which is where the pads are more useful than oodles of gain). Granted, i haven't tested anything in that direction, but on the other hand, you wouldn't use a dynamic mic on particularly quiet sound sources anyway (unless you really had no other choice), so there's that too.

So there we have it, a moderately detailed look inside a ~15 year old interface. Slight shame it won't be put to as much use as initially intended, due to another (even more useful) acquisition, but... Well, this can still be useful as a test-device and whatnot. Time will tell, but for now... Stay tuned for the foreshadowed next(?) teardown, wink-wink...

No comments:

Post a Comment